We should start this business!!!

(Business 2.0 Magazine) -- The editors have identified the Best business ideas in the world, which will appear here in a series throughout the next month. Check back daily for updates.

Think globalization means little more than call centers in New Delhi? Then you haven't seen what happens when seriously large numbers of Americans, who spend more than $570 billion at U.S. hospitals annually, start taking health-care holidays in far cheaper climes. Nor have you seen how much money there is to be made by helping them get there.

| |||

| |||

We're about to find out. This year alone, upwards of 500,000 Americans are expected to travel overseas to get their bodies fixed, at prices 30 to 80 percent less than at home.

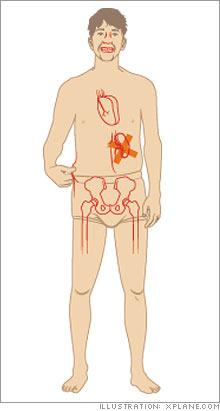

Medical tourism, as the practice is known, is rapidly becoming the top choice for consumers who grapple with hefty medical bills. Adult Americans who are either uninsured or considered "underinsured" number more than 61 million - a figure that's likely to soar in coming years.

With places like Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic, India, the Philippines, and Thailand pitching their low-cost care, Americans are expected to help turn global medical tourism into a $40 billion-a-year industry by 2010, according to David Hancock, author of The Complete Medical Tourist.

While disruptive to U.S.-based hospitals and HMOs, the overseas stampede is already spawning a brand-new business opportunity: medical tourism agencies. Not only do these companies act as middlemen between patients and foreign physicians, but they also find hospitals, schedule surgeries, buy airline tickets, reserve hotel rooms, and, yes, even plan sightseeing tours for recovering patients. Most important, they aim to reassure customers that cheap does not equal poor quality.

The best balm for anyone setting up a medical tourism agency is this: There are no licensing requirements, either in the United States or overseas. And thanks to free Internet phone services and online advertising, operating costs are relatively low.

"I see the market exploding," says Ted Mohr, an American who runs the Adventist Hospital in Penang, Malaysia, whose non-national customers now make up more than 30 percent of the institution's $32 million annual business (up from less than 5 percent a decade ago). "American health care is getting too expensive for too many people."

Europe, where Polish dentists advertise in in-flight magazines and budget airline Ryanair (Charts) promotes trips to cheap medical havens like Hungary, is ahead of the curve. But U.S. entrepreneurs are beginning to catch up.

MedRetreat, based in Odenton, Md., sent its first patient overseas two years ago. This year MedRetreat expects to ship 320 patients, mostly for cosmetic surgery, to partner hospitals in Brazil, Thailand, and Turkey. The average length of stay: 17 days.

Patrick Marsek, MedRetreat's managing director, says the company makes most of its money through commissions for booking hotel rooms and by pocketing the 20 percent discount on treatment costs that its partner hospitals grant in exchange for referrals.

Revenue is in the six-figure range, Marsek claims, adding that it will hit $1 million before long - especially now that he's looking to branch into more lucrative procedures like spinal fusions and hip resurfacings. "We're getting hundreds of inquiries a week," he says. "We've got our hands full." Marsek doesn't have any medical training.

Neither does Ken Erickson, who was running a fund-raising website in 2004 when a friend who owns call centers in India started talking about that country's first-rate private hospitals. Erickson, 44, hopped a plane to New Delhi, where he toured hospitals and met U.S.-trained doctors. His first thought: "My God, this is the perfect arbitrage situation. Buy below market and sell below market."

In May, Erickson founded GlobalChoice Healthcare, an Albuquerque, N.M., company with $1.5 million in angel funding and 14 employees. The startup has teamed up with medical providers in Costa Rica, India, Panama, and Singapore. It also has a deal with the five-star Taj Hotels Resorts and Palaces chain in India.

In June, GlobalChoice sent a patient to Punjab for a hip replacement that cost about $13,000, including airfare and a 20-day hotel stay. The estimated cost in the United States for the surgery alone? $40,000.

Erickson believes that the big money in medical tourism is in two markets: uninsured retirees ages 50 to 65 for whom Medicare hasn't yet kicked in, and self-insured companies that can no longer afford benefits for workers. He has met with Fortune 100 companies, though "they want to see the market mature first," he admits. If they do sign up, Erickson believes, he's sitting on a $500 million gold mine.

He has reason to be optimistic. Blue Ridge Paper Products, a Canton, N.C., paper manufacturer, may soon allow its 5,500 employees and dependents to go to India for certain company-insured treatments.

In West Virginia, a legislator is pushing a bill that would give incentives to state workers for seeking treatments overseas. "The early adoption has begun," says Arnold Milstein, a Mercer consultant hired by PlanetHospital, a Los Angeles-based medical referral startup, to strike deals to coordinate foreign-based care on behalf of employers and insurers.

To be sure, the medical tourism business is risky. A couple of surgical mishaps are all it would take for a company to lose its customer base. "This is a huge word-of-mouth business," says Sholto Ramsay, founder of Scotland-based Globe Health Tours, a year-old company that has seen a sixfold increase in business in the first six months of this year and will open a U.S. branch this fall.

That means companies like Ramsay's have to spend time and travel money meeting with hospital officials to verify the quality of care and negotiate prices. Hotels need to be outfitted for recuperating patients and have an English-speaking staff. Everything must go flawlessly. This is not a business for the faint of heart.

To thrive, an agency will need a broad presence around the world. Mohr, the Penang hospital CEO, recalls how its patient traffic plunged two years ago when a severe SARS outbreak kept foreigners out of Asia. "That hit us pretty hard," he says, even though business bounced back when the scare ended.

The fear of an epidemic or political unrest shutting down a region is one reason MedRetreat's Marsek is eager to build a strong global network. Another reason: U.S. employers and insurance companies will likely demand it. And what of lawsuits by disgruntled patients? After all, one reason U.S. health care is so expensive is its sky-high malpractice premiums.

Insurance companies don't yet offer medical tourism policies, so agencies like MedRetreat are hoping instead that broad customer waivers, plus an umbrella liability policy, will keep litigation in check. "A lot of companies will come and go," Erickson says. But if you can make it through the relapses, a hale and healthy startup life awaits.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home